- Home

- Michael Stone

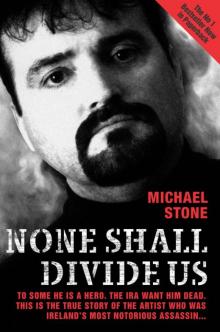

None Shall Divide Us

None Shall Divide Us Read online

In memory of Margaret Mary Gregg, née Stone

CONTENTS

Title Page

Dedication

INTRODUCTION

FOREWORD

THE BALLAD OF MICHAEL STONE

1 MARY AND CYRIL

2 A BOY FROM THE BRANIEL

3 STREET FIGHTER

4 FOR GOD AND ULSTER

5 TOMMY HERRON

6 RED HAND COMMANDO

7 NONE SHALL DIVIDE US

8 REPUBLICAN TARGETS

9 TAKING THE RAP

10 MARTIN MCGUINNESS

11 THE POPPY DAY MASSACRE

12 TOUTS INCORPORATED

13 THE BIG BALL IS ROLLING

14 CHAIN REACTION

15 MILLTOWN

16 YOU PLAY, YOU PAY

17 PRISONER A385

18 PAT FINUCANE

19 SHOW TRIAL

20 H-BLOCK 7

21 AGONY AUNT

22 MAD DOG, DAFT DOG, WEE JOHNNY, MR SHOWBIZ

23 THE ARTIST FORMERLY KNOWN AS RAMBO

24 LOYALIST CEASEFIRE

25 UNCHARTED WATERS

26 PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE

GLOSSARY

Copyright

INTRODUCTION

I FIRST HEARD OF MICHAEL STONE IN MARCH 1988. HIS ATTACK ON THE REPUBLICAN FUNERAL OF THREE IRA VOLUNTEERS SHOT DEAD IN GIBRALTAR IS SEARED ON MY BRAIN.

As a child of the Troubles, for me there are incidents, too many to mention, that stand out for their stark cruelty, their horror and their futility. Milltown is one of them. Although I was young, I could not believe a lone paramilitary would do such a thing. I could not believe a terrorist would gatecrash the funeral of three IRA volunteers killed on active service, but there he was, flat cap and all-weather jacket, lobbing grenades into the crowd and reaching inside his jacket and pulling out a handgun – live on television. I can still hear the crack as the gun was fired, the thuds as the grenades were launched, the sound of women screaming as they grabbed children. I can still see the faces of people as they dived for cover behind gravestones. I remember thinking that nothing, not even funerals, was sacred in the sick, perverted place I called home.

In the days immediately after the Milltown attack the newspapers had a field day about his one-man attack on a high-profile Republican funeral. It took just two days for the UDA, the organisation he joined when he was just sixteen years old, to denounce him. It took just two days for Michael Stone, Loyalist volunteer of seventeen, to lose his identity and become nothing more than labels such as ‘Rambo’, ‘nutter’, ‘loner’, ‘madman’, ‘killing machine’ and ‘robot’ – words used by the print media to describe him. I saw the TV footage and I agreed with their choice of vocabulary. The man was all of these things and more. Only someone insane would even entertain the idea of such a mission.

But sadly the story didn’t end at Milltown. It concluded three days later at the funeral of one of Michael’s victims, IRA volunteer Kevin Brady. Michael’s attack at Milltown was the flame which ignited one of the worst and most barbaric incidents of the entire troubles, the deaths of Corporals Derek Wood and David Howes. The young soldiers served with the Royal Corps of Signals, ironically Michael Stone’s great-grandfather’s regiment, and were executed on waste ground near the Andersonstown Road in West Belfast. The two were attacked by a forty-strong crowd after straying into Brady’s funeral cortège. The crowd attacked because they thought another Michael Stone was attacking them. Republicans heaped on the blame, saying it all went back to Stone’s assault, but to right-minded people it was just another senseless death in Ulster’s war.

I first met Michael Stone in August 2001. He had been released the previous year after serving twelve years of his life sentence for six murders and a variety of other charges, including attempted murder, conspiracy to murder and possession of firearms and explosives. While serving his sentence he began to paint and fell in love with this new pursuit, which gave him expression and focus in his lonely prison life. Within a year of walking from the Maze Prison a free man he had his first exhibition, in a small gallery in Belfast city centre. The work showcased some of his remarkable prison art, painted on the back of bedside lockers and wardrobe doors, and several post-release paintings. It was a proud moment for Michael Stone and his family, but he accepted with a sad heart that most of the people who turned up at the Engine Room Gallery on the Newtownards Road did so for ghoulish reasons. They wanted to see what sort of pictures a murderer paints, what price he sells them for and who in their right mind would have them. Michael caught my imagination.

I did have fears about meeting this man, a Loyalist folk icon revered in song and verse. I was anxious that my opinions of the man, formed twelve years earlier, would compromise my reactions. I made mental notes to be open-minded but I wasn’t prepared for the quiet man who limped down a flight of stairs to greet me; barely able to walk because of the hip injury he sustained in 1988. I was not prepared for the warm handshake that greeted my arrival. I was not prepared for the well-read and intelligent man who enjoys Irish politics and history. I was not prepared for the man who makes a daily superhuman effort to stay alive and admits he is more of a prisoner on the outside than he was inside the Maze.

Most of all, I was not prepared for the man who spoke poignantly about his past as a UDA volunteer and the part he played in the deaths of four men. Nor was I prepared for the man who has the sharpest memory I have ever come across and could recall every heartbeat of his volunteer life with precision. I didn’t anticipate liking Michael Stone, but I did.

To my critics, of whom I expect there will be plenty, I would say just one thing: I do not intend this book to be a glorification of the life of Michael Stone. I do not intend this book to glamorise his life as a paramilitary. The book’s objective is to show what happens to young men, both Protestant and Catholic, who get sucked into sectarian warfare. It is Michael Stone’s story, but it is also the story of a handful of men who lived, and sadly continue to live, similar lives.

Michael Stone’s story is shocking but it needs to be told. It will show him to be more than the tabloid labels, more than Rambo, the volunteer, the killer, the crazed gunman, the prisoner and the artist. This is Michael’s story.

Karen McManus, 2004

FOREWORD

I AM A PROUD LOYALIST AND THIS WILL NEVER CHANGE. IT IS A STATEMENT OF FACT, NOT A DEFIANT SALUTE. I am British and I am a Loyalist and will be both of these things until I die. At the age of sixteen I put myself forward for a cause I believed in with all my heart. I remain proud of that fact but I am not proud of my actions. I am not proud that four men died by my hand.

I grew up with a sectarian war on my doorstep and I couldn’t watch evil things being done, such as Enniskillen, La Mon and the Abercorn, and not do something about it. It is impossible for me to think that I would have never become a volunteer. Before long, terrorism became a way of life for me. I lived on the edge. I knew what my capabilities were. I knew I had the power to take life and to grant mercy, but I was never indiscriminate, unlike the Provisional IRA.

This book is an attempt to explain my actions as a volunteer and a retaliatory soldier. By committing the story of my life to paper, I am taking responsibility for my past. I am acknowledging that I caused pain to four families when I took their loved one away from them.

To the families of Patrick Brady, Thomas McErlean, John Murray and Kevin Brady I am sorry for your loss. I am sorry that you never got to say goodbye to your son, husband, boyfriend, father and brother because of me. I deeply regret the hurt I caused the families of the men I killed. I regret that I had to kill. I believed at the time that it was necessary. There is nothing I can do to take away the pain I have inflicted. There

is a lot of hurt out there and I am responsible. Much of that hurt comes from my actions as a paramilitary. I don’t see myself as a criminal. I committed crimes as an Ulsterman and a British citizen and that was regrettable but unavoidable.

To the families of Kevin McPolin and Dermot Hackett I am also sorry for your loss.

I didn’t choose killing as a career; killing chose me. I hated bullies. When I was a young boy and saw someone being bullied at school or work, I always stepped in. As I grew older and started to form opinions, I realised Republicans were bullies, nothing more and nothing less, who took life after innocent life and no one seemed interested in stopping them. I put myself forward as a volunteer, thinking my actions could change things.

This book is also an attempt to explain the bigger picture: why young men from my community felt duty-bound to take up arms. It is a shocking account of the grim business I was engaged in for almost thirty years. There is nothing romantic about taking a life in defence of your community. It is a cold and brutal act. When a person dies, a little part of you dies too. I want to share that horror as a reminder that we must never look back. All of us must keep our eyes fixed on the road ahead, not the dark paths behind us.

Maturity is a wonderful gift. It is only now as I face the autumn of my life that I really understand. I understand what motivated Republicans. They saw grave injustices being perpetrated on their community and they lashed out. They were angry young Catholic men and no different from me, an angry young Protestant man who saw terrible crimes being perpetrated on his community.

I committed some terrible crimes over the years and I did it in the name of Ulster and in the name of my Britishness. Republicans committed some terrible crimes over the years and they did it in the name of their Irishness. That’s the nature of the beast we call war.

Looking back, I can hardly believe that I did those things and lived the life I led. It is like peering into the life of a stranger. But it is my history, the history of Michael Anthony Stone. The person who emerges from these pages is not likeable and he is not attractive. This book shows a young man eaten up with anger and filled with hate for anonymous names on intelligence files. It shows a ruthless man, dedicated to his cause and ready to take life for what he believed in.

This is a true account of my life as a Loyalist volunteer. It is a shock to revisit my past, and writing this book has brought it all back. I have also realised that you can’t kill a political persuasion, just a human being. You can’t kill an identity, just a much-missed father and son. These people live on in their loved ones.

My war is over. I am no longer willing or able to take a life for what I believe in. I am like an old dinosaur. I hope I can slip into obscurity, but I honestly believe I will die as I lived, with a bullet in my head. When it comes, I hope my death is quick and I hope it is over in seconds. I also hope none of my family or friends are with me when it happens. An old paramilitary saying comes to mind:

If I go forward I die.

If I go back I die.

I’ll go forward and die.

Michael Stone

May 2004

The Ballad of Michael Stone

Three taigs flew into Dublin

On a big Gibraltan plane

The Provos planned to bury them

With honour and with fame

The Fenians they were out in force

To see that all went well

But the bravery of a Loyalist

Did shame them all to hell

Michael Stone he was the brave young man

From the Braniel he did come

Who thwarted all the Provos’ plans

And killed the rebel scum

With handgun and grenades

He dealt the deadly blow

And the PIRA didn’t get to have

Their paramilitary show

The brave young Proddy came

From the east end of the town

He infiltrated West Belfast

And didn’t let us down

He stood and did the business

I’m sure you’ll all agree

And the day before St Paddy’s Day

Went down in history

1

MARY AND CYRIL

I CAME INTO THE WORLD ON 2 APRIL 1955 IN LORDSWOOD HOSPITAL, HARBORNE, BIRMINGHAM, THE FIRST-BORN CHILD OF MARY BRIDGET AND CYRIL STONE. I am a British citizen and proud to be one. I have always cherished my nationality. My family history is complex, but it forms the backbone of my identity. I have two sets of parents: my biological mother and father, Mary Bridget O’Sullivan and her husband Cyril Alfred Stone, and the parents who raised me as their own, Margaret and John Gregg.

I know very little about my biological mother. Mary Bridget O’Sullivan is an Irish name but I do not know if she was an Irish citizen. All I do know is that she spoke with a strong English accent. Mary Bridget was the eldest child in a very large family. Her own mother died when she was very young and she was charged with raising her younger brothers and sisters. My biological father was born in the United Kingdom but spoke with an accent straight from the Shankill Road. He lived in England all his life yet his accent was as strong as if he lived in the heart of West Belfast.

Mary Bridget and Cyril met in the UK and were married at Caxton Hall registry office, London, in 1953. She was just eighteen and he just twenty-one when they exchanged vows. The union lasted only two years, enough time for Mary Bridget to decide motherhood and marriage weren’t for her. She walked out on her husband and new baby in September 1955, when I was just five months old. Mary Bridget never again saw the baby boy she left in Cyril’s arms. A restless Jack the Lad, Cyril took just minutes to plan his next move: the boat to Belfast to his only sister, Margaret, and her new husband, John, who lived in Ballyhalbert, on the shores of Belfast Lough. He handed his son into the care of the young couple, who raised me as their own, turned on his heels and joined the Merchant Navy.

Margaret and John are the only parents I have ever known. Margaret was the best mother a young boy could wish for. She died in 2001 from heart complications. My father John spent his final years in a nursing home surrounded by ladies who want to marry him. He died in April 2003.

I have just the one photograph of Cyril and Mary Bridget together. It is a symbol of who I am and a poignant reminder that two people brought me into the world but played no part in my upbringing. Yet I am still drawn to them like a nail to a magnet. I am curious about Mary Bridget. I want to know what went on in 1955 when she called time on our little family. The photograph shows a beautiful young girl with dark curls framing her delicate features and wearing smart clothes. She is linking arms with a swarthy man in an overcoat. They look happy. Both are smiling at the camera but I wonder what was going on beneath the surface. When they met, Cyril was a member of the Forces, a full-time reservist in the RAF. By the time I was born, he was driving lorries for a chemical firm, a job which took him all over the UK.

My mother had sparse details about their relationship. She told me Cyril was quick-tempered and possessive and Mary Bridget liked her freedom. It was a stormy marriage and destined to fail. Just a few years before my mother died she told me she met Mary Bridget once. Mum described her as a beautiful and gentle girl who was like a little bird – she just wanted to fly away. That is the memory I carry of the woman who brought me into the world: a little bird who saw her chance of freedom and grabbed it.

I have searched all my adult life for Mary Bridget O’Sullivan, but she has vanished off the face of the earth. I have tried everywhere to find her. Even the Red Cross couldn’t help me. Nothing exists after 1955, when my birth was registered. I do regret that I never got to meet Mary Bridget and she knows nothing about the man I became. I do not know what happened to her. She could be dead, she could have remarried or she could have emigrated to America or Australia. I still would like to see her and ask her about her life. I would like to tell her about my own life and would be happier doing this now my own mother is dead

. I wouldn’t feel that I was betraying my own mother by speaking to Mary Bridget.

My entry into the world was rarely talked about at home. My mother resented Mary Bridget for abandoning her baby and walking out on her family. Mum was old-fashioned. She believed a woman’s place was with her children and in the home. From a very young age I was aware that I had a different surname from my brother and sisters, but there was no question of Mum allowing me to change my name from Stone to Gregg. I would ask tentative questions about why my name was different, but the only answer I got was: ‘Let sleeping dogs lie.’ I never probed. I didn’t want to seem ungrateful or unfaithful because I loved her.

My mother was proud of her maiden name and she constantly said to me, ‘Be proud of your name because your married parents gave it to you.’

I am not interested in Mary Bridget’s religion, and religious persuasion is not an issue for me. She may have been a Roman Catholic or she may not have been. It doesn’t matter. Mary Bridget gave birth to me but she didn’t bring me up. Margaret Gregg raised me as her son and within days of my arrival in Northern Ireland had me baptised into the Anglican faith.

When I first put those tentative questions about my biological father, Mum told me that he ‘lived far away’. I know she did that to protect me and to make it sound like I hadn’t been dumped as a newborn child. Cyril Stone was my mother’s only brother and he kept in constant contact over the years, making regular enquiries about his first-born’s development. Years later, when I was a grown man, I discovered my mother even sent the odd school photograph to Cyril, who was now living in Birmingham, and he kept all those pictures and placed them side by side with photos of his second family.

I was eleven when my mother decided it was time I knew about my background. She had the perfect opportunity. I was enrolling at secondary school and she feared that if I didn’t know the facts I would be bullied and ridiculed in the playground. My elder sisters, Rosemary and Colleen, and elder brother, John, were already pupils there. Just days before I was due to enrol I was handed an old shoebox. Inside there was a bundle of letters and telegrams. They were all addressed to me, had postmarks stretching over an eleven-year period and were stamped with various exotic addresses such as ‘Gibraltar Port’. At first I was bewildered. My mother said one thing: ‘These letters are from Cyril Stone, who is your father. He is an officer in the Merchant Navy.’ The letters are dog-eared and torn around the folds. It proved to me that Cyril Alfred Stone felt something in his heart for the little boy he handed into the care of his sister in the autumn of 1955.

Streeter Box Set

Streeter Box Set Low End of Nowhere

Low End of Nowhere The Expanse

The Expanse None Shall Divide Us

None Shall Divide Us